Rococo – as specific and attractive as its name, is a combination of art, politics, thirst for passion and lust. Every of the above-mentioned keywords define the 18th-century movement in art. Rococo,...

Rococo – as specific and attractive as its name, is a combination of art, politics, thirst for passion and lust. Every of the above-mentioned keywords define the 18th-century movement in art. Rococo, from the French word rocaille, meaning “shell and rock garden ornamentation,” also known as “Late Baroque,” is a reaction to the Baroque itself. What preceded the Rococo style, in the eyes of the artists, was seen as death to the freedom of expression and the source of all artistic limitations. Louis XIV’s longing to emphasize his dominance and the eminence of France has been shown through the grand and formal artworks of the seventeenth-century French art. Baroque was the “slave” of this “glorifying power and politics” art, used to express the King’s pompousness.

In 1715 the French people welcomed their new king; Louis XV, a kid just five years of age succeeded his granddad Louis XIV, the Sun King, who had made France the superior force in Europe. His ravenousness for magnificence and vivaciousness was immense, so he put aside the devotion at Versailles and the strict art upheld and earlier used by Louis XIV to express the King’s power. France moved in the opposite direction of supreme desires, to concentrate on more individual and pleasurable interests. As political life and private ethics loosened, the change was reflected by another style in craftsmanship, one that was personal, brightening, and frequently erotic. The Rococo style was born. Starting with the decorative arts, Rococo emphasized pale and subtle colors, curves, and patterns mostly covered with motifs of flowers, vines, and shells. Painters turned from grandiosity to the exotic surface pleasures of shading and light, and from profound religious and historical subjects—however, these were never disregarded totally—to more personal legendary scenes, perspectives of everyday life, and picture.

The one, in which artists went farthest in the Rococo era, was the liberation to present eroticism in a different way, however, very courageous of them in this period. Running away from the political rules and frames, Rococo has awakened the passion in humans; not that people before weren’t sexually conscious, but art gave them what they couldn’t afford – freedom. Pride, power, and the figure of a lady, except being synonymous with royal France, have now become a synonym with the works of Rococo style too. Eroticism is taken at a high level; it is not displayed only through pure nudity, on the contrary, the Rococo style is rich in erotic clothing, and some naked parts of the body. Eroticism is a symbol of passion, lustful and emotional storms, sexuality, sexual desires, dreams, and fantasies. Rococo erotica is the longing of a bourgeois French lady, boost to the male organ and orgasm for the mind of the artist.

This artistic style is witty and cunning; on one hand, there are the innocence and simplicity of French life shown by pastel colors and the use of refined, disenchanted ornaments, while the other side shows “sweet debauchery.” We do not see the Sodom and Gomorrah led by courtesans, royal servants, and dependents; so clearly, Rococo style gives us a picture of a quiet, peaceful France. If we go a little deeper and further, we can realize that the pastel colors and powder pink roses are perhaps a symbol of women’s bare skin. Lush gardens and fountains are the splendor of a woman hidden under long ball and masquerade dresses.

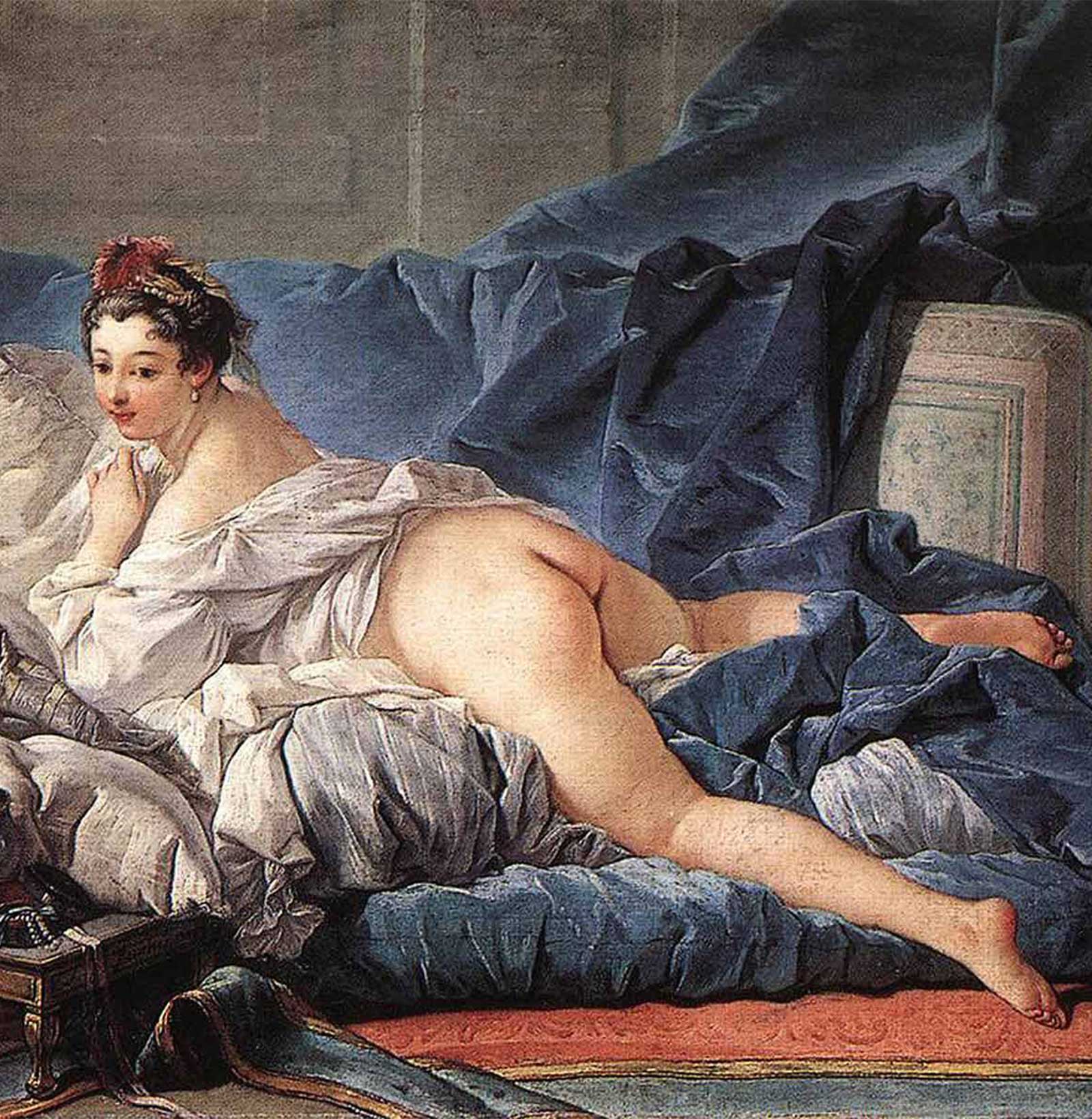

The Golden Three of Rococo are the artists: Antoine Watteau, Francois Boucher and Jean-Honore Fragonard – the only three who looked at baroque in the face and instead of following the king’s terms, embraced eroticism as their eternal love. Watteau’s courage is seen in the fête Galante paintings, in which he showed the ludic and erotic side of the French aristocracy. A good example of “dressed erotica” is his picture Le faux pas (1717) that screams out sexual desire, passion, seduction and love.

Boucher was the erotic “messenger” in Rococo style.

He enjoyed painting the female body, as it is; curvy, exuberant and naked. Through the painting of his female acquaintances or wife, Boucher expresses femininity and passion.

In the end, Fragonard knew how to play with the mind and the eye of the consumers of his art; The Swing, his most famous work, shows a seemingly ordinary day for the French bourgeoisie. A woman enjoying a swing with her servant and in front of her lays a man whose gaze is directed under her skirt. This covered eroticism tickles the imagination; what is hidden in the minds of the two lovers? Many “cat and mouse” games are used in the art of Rococo. Pastel colors, beautiful gardens and lush flowers cover the then erotic entertainment. The baroque political cunning and desire for power were then replaced by a thirst for passion and sharing of sex secrets.