Always one to make waves with his art, Picasso made one of the biggest splashes of his career in 1916, with the debut of a large, provocative canvas at a leading modern art exhibition. His colleagues and...

Always one to make waves with his art, Picasso made one of the biggest splashes of his career in 1916, with the debut of a large, provocative canvas at a leading modern art exhibition. His colleagues and critics celebrated the painting as the dawn of Cubism, an innovative painting approach that secured Picasso’s position in the pantheon of artistic greats. While it heralded a new era in artistic ingenuity, it was more importantly also an erotically charged work. Known today as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907, Museum of Modern Art), this composition depicted a brothel scene filled with nudes.

Picasso invoked erotic themes throughout his career, from tasteful nude studies to more sexually explicit vignettes. During the early years of the twentieth century, the erotic played a particularly significant role in Picasso’s exploration of himself. This exploration of eroticism as a means of self-reflection opened new doors for artistic innovation. It gave new intensity to images with sexual implications and revealed their potential to be powerful reflections of one’s own experiences. So, while Picasso is firmly established as a founder of modernity, he can also be credited with creating a new place for eroticism in twentieth-century art.

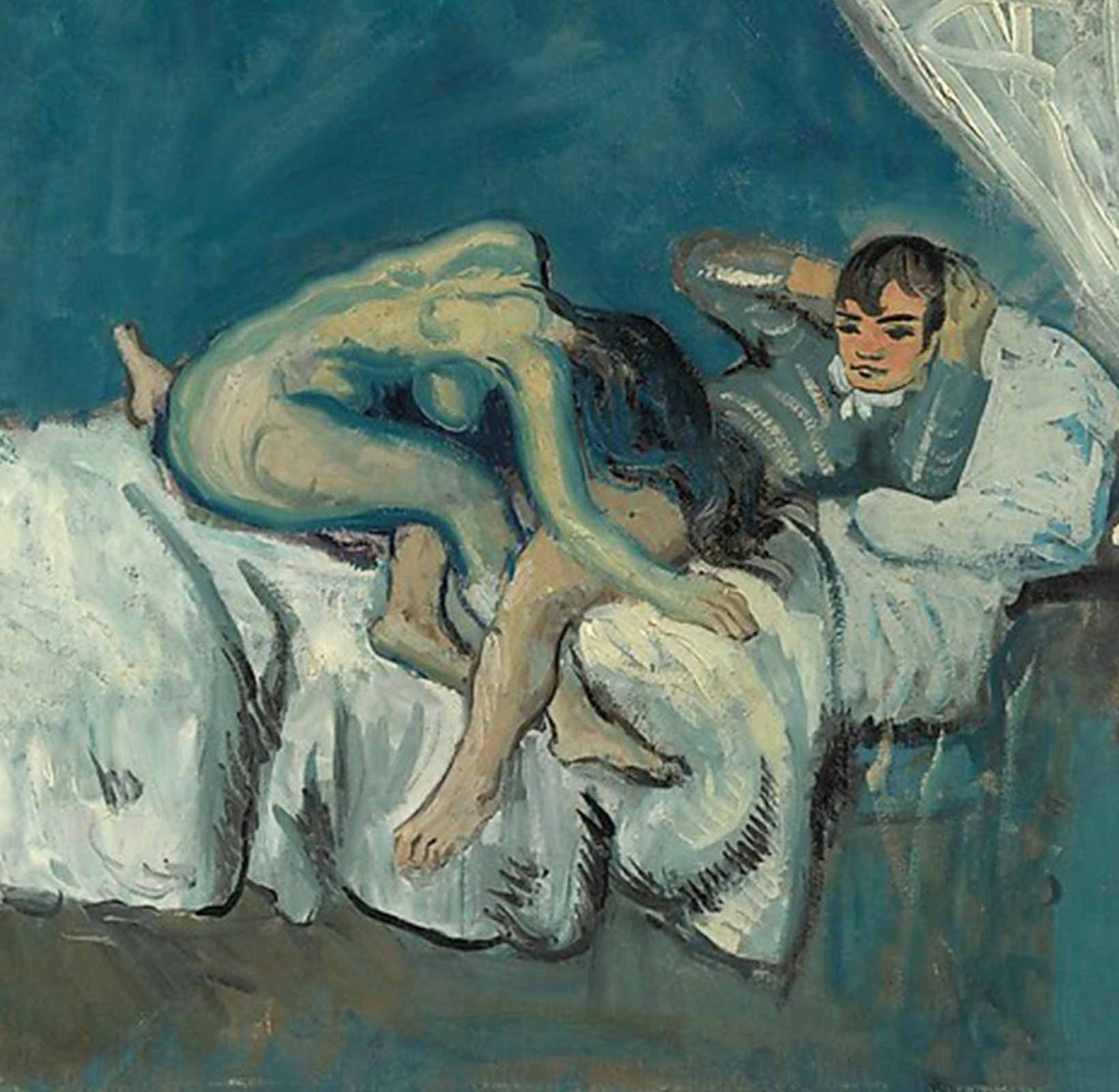

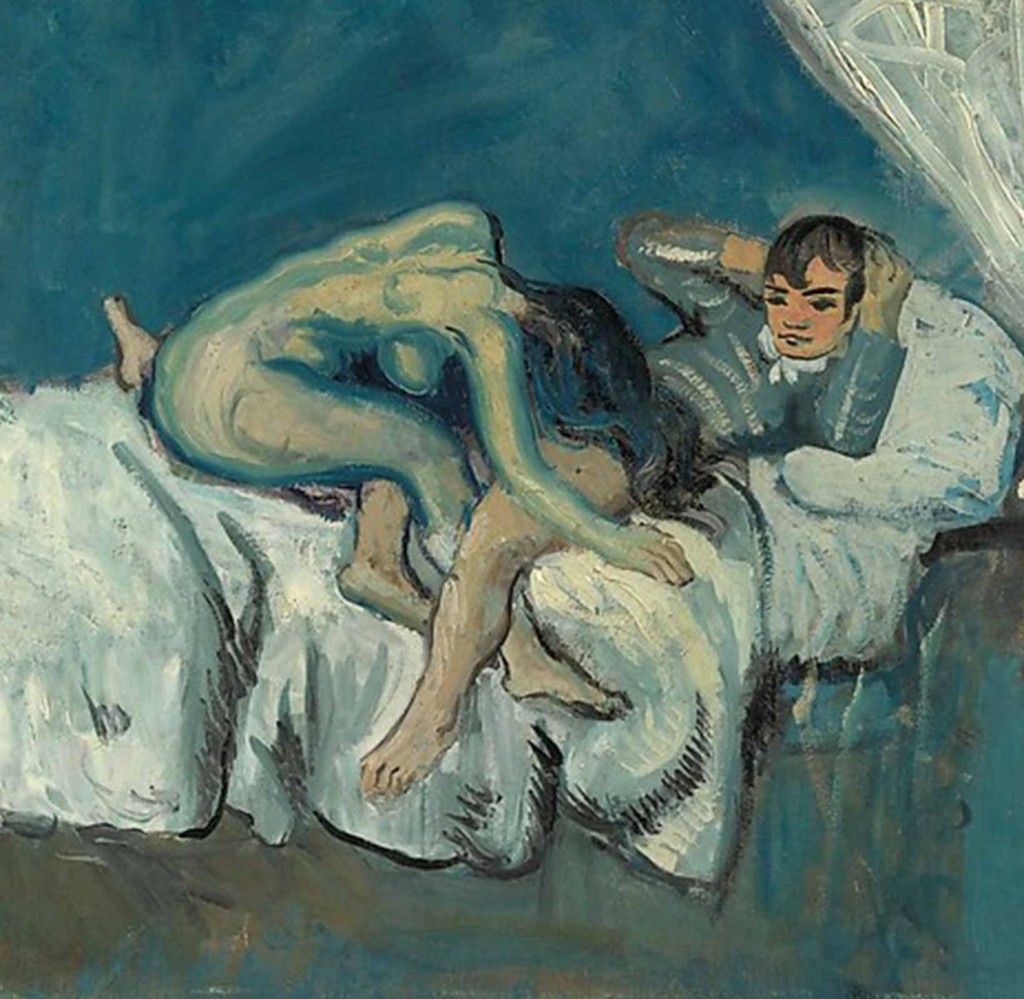

At the turn of the century, Picasso, barely in his twenties, began experimenting with different approaches to painting. The first half of the first decade of the twentieth century was dominated with his experimentation with color through his Blue Period (1901-1904) and Rose Period (1904-1906). It is during these years that one can sense the initial impact of the erotic in Picasso’s paintings. In 1903, for example, he completed a small oil painting entitled La Douceur (1903; Metropolitan Museum of Art), a boudoir picture that is rendered in the cool blues typical of his Blue Period. It is also a rather suggestive image, both in that Picasso painted a particular sexual act being performed and also that he used his own self-portrait to depict the recipient of this sexual favor. He positions himself as somewhat detached from the act that is occurring, instead of propping himself up and gazing rather confidently at the viewer. While this posture can be seen as Picasso’s quotation of his art-historical heritage (The Metropolitan, for example, draws parallels between this pose and that seen in some compositions by Francisco Goya, one of Picasso’s idols), it also suggests a certain level of bravura and biography on the part of the artist, as he was a rather wanton youth.

Picasso’s shift toward experimentation with composition and form in late 1906 and early 1907 resulted in the development of Cubism, an artistic approach that generally involved the breakdown of figural and material forms into geometric planes or facets of color. Even while undergoing these more technical innovations, Picasso continued to incorporate erotic references. Indeed, some of these earliest Cubist explorations focus on compositions of women with amorous or erotic connections. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is a prime example, as it reveals five prostitutes supposedly staged in a brothel interior. Their naked bodies are rendered as facets, or planes of color, while their faces dissolve into a certain level of asymmetry or disfigurement. This is most pronounced in the two right-hand figures, whose faces were reworked into emulations of African masks. The grittiness of this masked figure in the foreground is exacerbated by her rather vulgar squatting position as she looks directly out at the viewer.

The erotic played a significant role in Picasso’s exploration of himself.

While Picasso could be examining his own profligate sexuality here, one can also say that this painting reflects Picasso’s own tumultuous relationship with model-turned-lover Fernand Olivier. The two had met and fell in love in 1904, but their liaison was plagued with jealously that resulted in consistent bickering and, eventually, their separation. Picasso’s love for Fernand, and perhaps also his desire to better understand her, is reflected pronouncedly in his early Cubist works, and it seems not coincidental that it was when Picasso and Fernand parted ways in 1907 that he returned to Demoiselles d’Avignon and changed the two women on the right into masked figures. While only Picasso knows exactly why he incorporated these changes, one can suggest that he did so in direct response to Fernand’s departure. Thus, the eroticism of the scene is tempered with Picasso’s personal frustration between sex, love, and life.

For more discussion of Picasso’s erotic art, please look to Picasso Érotique, the comprehensive catalog from the 2001 exhibition organized by the French Réunion des Musées Nationaux that featured over 350 works on an erotic theme from Picasso’s oeuvre.